In an earlier article, we looked at an overview of caching in Django and took a dive into how to cache a Django view along with using different cache backends. This article looks closer at the low-level cache API in Django.

--

Django Caching Articles:

- Caching in Django

- Low-Level Cache API in Django (this article!)

Contents

Objectives

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Set up Redis as a Django cache backend

- Use Django's low-level cache API to cache a model

- Invalidate the cache using Django database signals

- Simplify cache invalidation with Django Lifecycle

- Interact with the low-level cache API

Django Low-Level Cache

Caching in Django can be implemented on different levels (or parts of the site). You can cache the entire site or specific parts with various levels of granularity (listed in descending order of granularity):

- Per-site cache

- Per-view cache

- Template fragment cache

- Low-level cache API

For more on the different caching levels in Django, refer to the Caching in Django article.

If Django's per-site or per-view cache aren't granular enough for your application's needs, then you may want to leverage the low-level cache API to manage caching at the object level.

You may want to use the low-level cache API if you need to cache different:

- Model objects that change at different intervals

- Logged-in users' data separate from each other

- External resources with heavy computing load

- External API calls

So, Django's low-level cache is good when you need more granularity and control over the cache. It can store any object that can be pickled safely. To use the low-level cache, you can use either the built-in django.core.cache.caches or, if you just want to use the default cache defined in the settings.py file, via django.core.cache.cache.

Project Setup

Clone down the base project from the django-low-level-cache repo on GitHub:

$ git clone -b base https://github.com/testdrivenio/django-low-level-cache

$ cd django-low-level-cache

Create (and activate) a virtual environment and install the requirements:

$ python3.9 -m venv venv

$ source venv/bin/activate

(venv)$ pip install -r requirements.txt

Apply the Django migrations, load some product data into the database, and the start the server:

(venv)$ python manage.py migrate

(venv)$ python manage.py seed_db

(venv)$ python manage.py runserver

Navigate to http://127.0.0.1:8000 in your browser to check that everything works as expected.

Cache Backend

We'll be using Redis for the cache backend.

Download and install Redis.

If you’re on a Mac, we recommend installing Redis with Homebrew:

$ brew install redis

Once installed, in a new terminal window start the Redis server and make sure that it's running on its default port, 6379. The port number will be important when we tell Django how to communicate with Redis.

$ redis-server

For Django to use Redis as a cache backend, the django-redis dependency is required. It's already been installed, so you just need to add the custom backend to the settings.py file:

CACHES = {

'default': {

'BACKEND': 'django_redis.cache.RedisCache',

'LOCATION': 'redis://127.0.0.1:6379/1',

'OPTIONS': {

'CLIENT_CLASS': 'django_redis.client.DefaultClient',

}

}

}

Now, when you run the server again, Redis will be used as the cache backend:

(venv)$ python manage.py runserver

Turn to the code. The HomePageView view in products/views.py simply lists all products in the database:

class HomePageView(View):

template_name = 'products/home.html'

def get(self, request):

product_objects = Product.objects.all()

context = {

'products': product_objects

}

return render(request, self.template_name, context)

Let's add support for the low-level cache API to the product objects.

First, add the import to the top of products/views.py:

from django.core.cache import cache

Then, add the code for caching the products to the view:

class HomePageView(View):

template_name = 'products/home.html'

def get(self, request):

product_objects = cache.get('product_objects') # NEW

if product_objects is None: # NEW

product_objects = Product.objects.all()

cache.set('product_objects', product_objects) # NEW

context = {

'products': product_objects

}

return render(request, self.template_name, context)

Here, we first checked to see if there's a cache object with the name product_objects in our default cache:

- If so, we just returned it to the template without doing a database query.

- If it's not found in our cache, we queried the database and added the result to the cache with the key

product_objects.

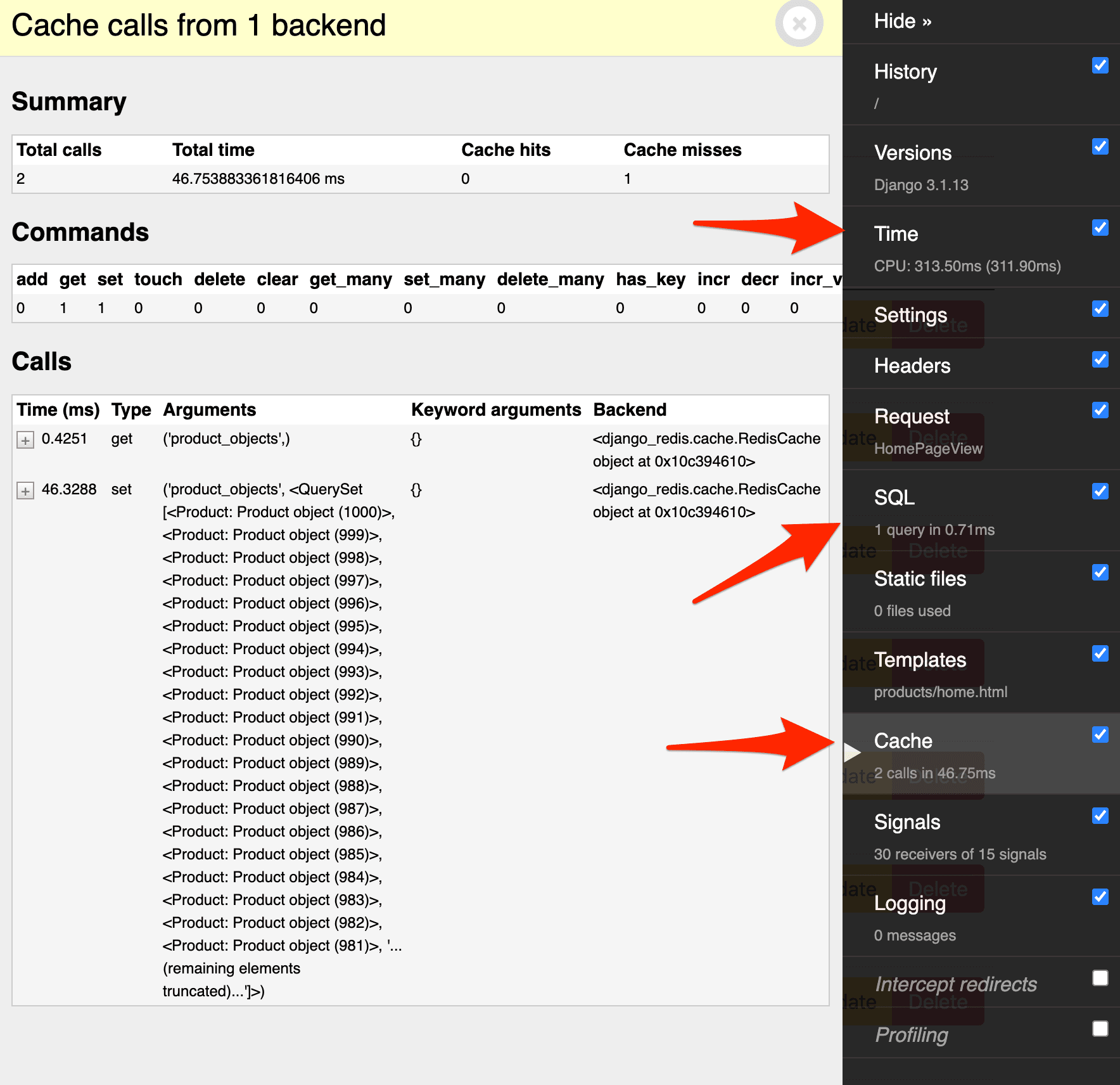

With the server running, navigate to http://127.0.0.1:8000 in your browser. Click on "Cache" in the right-hand menu of Django Debug Toolbar. You should see something similar to:

There were two cache calls:

- The first call attempted to get the cache object named

product_objects, resulting in a cache miss since the object doesn't exist. - The second call set the cache object, using the same name, with the result of the queryset of all products.

There was also one SQL query. Overall, the page took about 313 milliseconds to load.

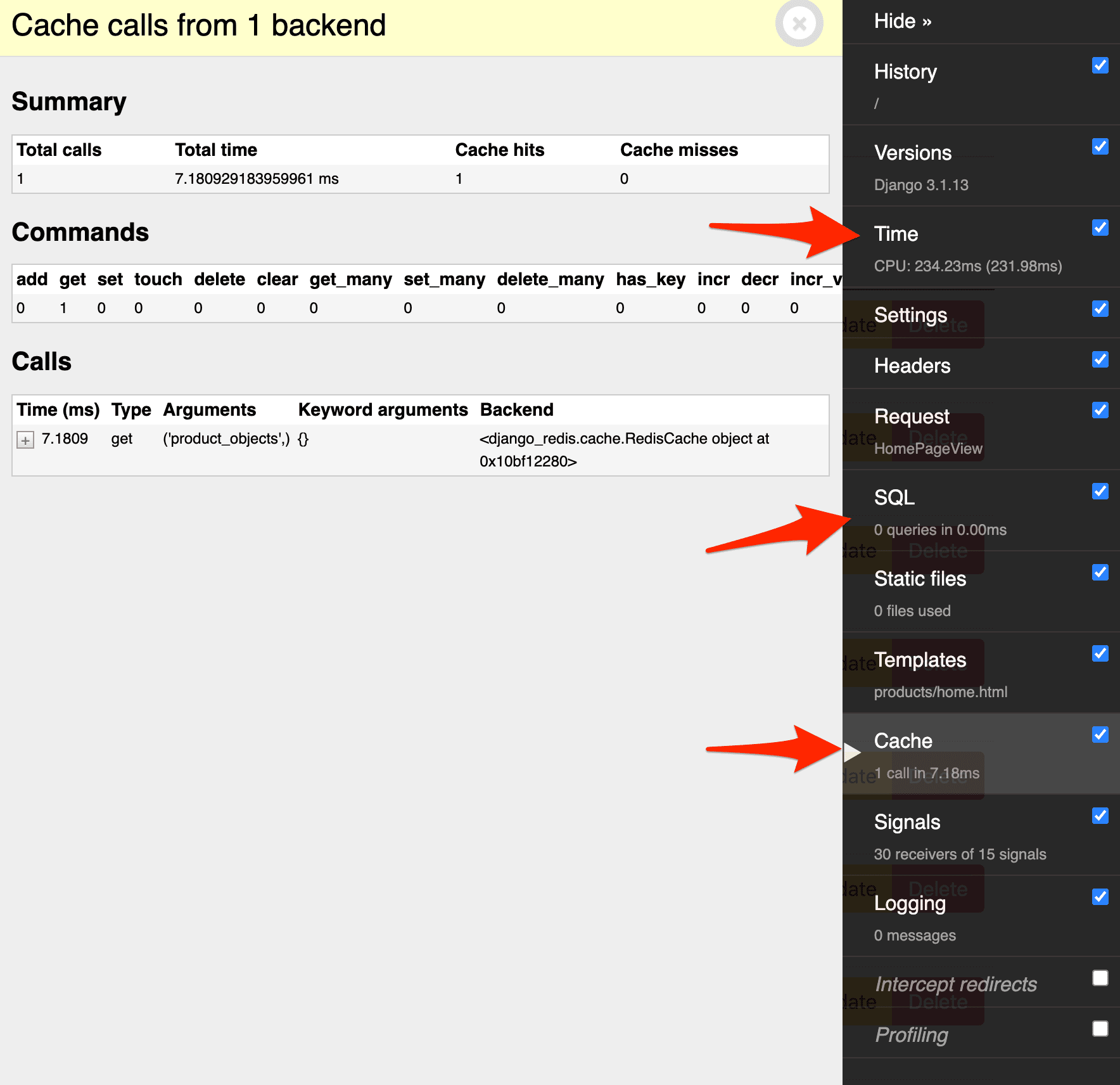

Refresh the page in your browser:

This time, you should see a cache hit, which gets the cache object named product_objects. Also, there were no SQL queries, and the page took about 234 milliseconds to load.

Try adding a new product, updating an existing product, and deleting a product. You won't see any of the changes at http://127.0.0.1:8000 until you manually invalidate the cache, by pressing the "Invalidate cache" button.

Invalidating the Cache

Next let's look at how to automatically invalidate the cache. In the previous article, we looked at how to invalidate the cache after a period of time (TTL). In this article, we'll look at how to invalidate the cache when something in the model changes -- e.g., when a product is added to the products table or when an existing product is either updated or deleted.

Using Django Signals

For this task we could use database signals:

Django includes a “signal dispatcher” which helps decoupled applications get notified when actions occur elsewhere in the framework. In a nutshell, signals allow certain senders to notify a set of receivers that some action has taken place. They’re especially useful when many pieces of code may be interested in the same events.

Saves and Deletes

To set up signals for handling cache invalidation, start by updating products/apps.py like so:

from django.apps import AppConfig

class ProductsConfig(AppConfig):

name = 'products'

def ready(self): # NEW

import products.signals # NEW

Next, create a file called signals.py in the "products" directory:

from django.core.cache import cache

from django.db.models.signals import post_delete, post_save

from django.dispatch import receiver

from .models import Product

@receiver(post_delete, sender=Product, dispatch_uid='post_deleted')

def object_post_delete_handler(sender, **kwargs):

cache.delete('product_objects')

@receiver(post_save, sender=Product, dispatch_uid='posts_updated')

def object_post_save_handler(sender, **kwargs):

cache.delete('product_objects')

Here, we used the receiver decorator from django.dispatch to decorate two functions that get called when a product is added or deleted, respectively. Let's look at the arguments:

- The first argument is the signal event in which to tie the decorated function to, either a

saveordelete. - We also specified a sender, the

Productmodel in which to receive signals from. - Finally, we passed a string as the

dispatch_uidto prevent duplicate signals.

So, when either a save or delete occurs against the Product model, the delete method on the cache object is called to remove the contents of the product_objects cache.

To see this in action, either start or restart the server and navigate to http://127.0.0.1:8000 in your browser. Open the "Cache" tab in the Django Debug Toolbar. You should see one cache miss. Refresh, and you should have no cache misses and one cache hit. Close the Debug Toolbar page. Then, click the "New product" button to add a new product. You should be redirected back to the homepage after you click "Save". This time, you should see one cache miss, indicating that the signal worked. Also, your new product should be seen at the top of the product list.

Updates

What about an update?

The post_save signal is triggered if you update an item like so:

product = Product.objects.get(id=1)

product.title = 'A new title'

product.save()

However, post_save won't be triggered if you perform an update on the model via a QuerySet:

Product.objects.filter(id=1).update(title='A new title')

Take note of the ProductUpdateView:

class ProductUpdateView(UpdateView):

model = Product

fields = ['title', 'price']

template_name = 'products/product_update.html'

# we overrode the post method for testing purposes

def post(self, request, *args, **kwargs):

self.object = self.get_object()

Product.objects.filter(id=self.object.id).update(

title=request.POST.get('title'),

price=request.POST.get('price')

)

return HttpResponseRedirect(reverse_lazy('home'))

So, in order to trigger the post_save, let's override the queryset update() method. Start by creating a custom QuerySet and a custom Manager. At the top of products/models.py, add the following lines:

from django.core.cache import cache # NEW

from django.db import models

from django.db.models import QuerySet, Manager # NEW

from django.utils import timezone # NEW

Next, let's add the following code to products/models.py right above the Product class:

class CustomQuerySet(QuerySet):

def update(self, **kwargs):

cache.delete('product_objects')

super(CustomQuerySet, self).update(updated=timezone.now(), **kwargs)

class CustomManager(Manager):

def get_queryset(self):

return CustomQuerySet(self.model, using=self._db)

Here, we created a custom Manager, which has a single job: To return our custom QuerySet. In our custom QuerySet, we overrode the update() method to first delete the cache key and then perform the QuerySet update per usual.

For this to be used by our code, you also need to update Product like so:

class Product(models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=200, blank=False)

price = models.CharField(max_length=20, blank=False)

created = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

updated = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

objects = CustomManager() # NEW

class Meta:

ordering = ['-created']

Full file:

from django.core.cache import cache

from django.db import models

from django.db.models import QuerySet, Manager

from django.utils import timezone

class CustomQuerySet(QuerySet):

def update(self, **kwargs):

cache.delete('product_objects')

super(CustomQuerySet, self).update(updated=timezone.now(), **kwargs)

class CustomManager(Manager):

def get_queryset(self):

return CustomQuerySet(self.model, using=self._db)

class Product(models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=200, blank=False)

price = models.CharField(max_length=20, blank=False)

created = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

updated = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

objects = CustomManager()

class Meta:

ordering = ['-created']

Test this out.

Using Django Lifecycle

Rather than using database signals, you could use a third-party package called Django Lifecycle, which helps make invalidation of cache easier and more readable:

This project provides a @hook decorator as well as a base model and mixin to add lifecycle hooks to your Django models. Django's built-in approach to offering lifecycle hooks is Signals. However, my team often finds that Signals introduce unnecessary indirection and are at odds with Django's "fat models" approach.

To switch to using Django Lifecycle, kill the server, and then update products/app.py like so:

from django.apps import AppConfig

class ProductsConfig(AppConfig):

name = 'products'

Next, add Django Lifecycle to requirements.txt:

Django==3.1.13

django-debug-toolbar==3.2.1

django-lifecycle==0.9.1 # NEW

django-redis==5.0.0

redis==3.5.3

Install the new requirements:

(venv)$ pip install -r requirements.txt

To use Lifecycle hooks, update products/models.py like so:

from django.core.cache import cache

from django.db import models

from django.db.models import QuerySet, Manager

from django_lifecycle import LifecycleModel, hook, AFTER_DELETE, AFTER_SAVE # NEW

from django.utils import timezone

class CustomQuerySet(QuerySet):

def update(self, **kwargs):

cache.delete('product_objects')

super(CustomQuerySet, self).update(updated=timezone.now(), **kwargs)

class CustomManager(Manager):

def get_queryset(self):

return CustomQuerySet(self.model, using=self._db)

class Product(LifecycleModel): # NEW

title = models.CharField(max_length=200, blank=False)

price = models.CharField(max_length=20, blank=False)

created = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

updated = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

objects = CustomManager()

class Meta:

ordering = ['-created']

@hook(AFTER_SAVE) # NEW

@hook(AFTER_DELETE) # NEW

def invalidate_cache(self): # NEW

cache.delete('product_objects') # NEW

In the code above, we:

- First imported the necessary objects from Django Lifecycle

- Then inherited from

LifecycleModelrather thandjango.db.models - Created an

invalidate_cachemethod that deletes theproduct_objectcache key - Used the

@hookdecorators to specify the events that we want to "hook" into

Test this out in your browser by-

- Navigating to http://127.0.0.1:8000

- Refreshing and verifying in the Debug Toolbar that there's a cache hit

- Adding a product and verifying that there's now a cache miss

As with django signals the hooks won't trigger if we do update via a QuerySet like in the previously mentioned example:

Product.objects.filter(id=1).update(title="A new title")

In this case, we still need to create a custom Manager and QuerySet as we showed before.

Test out editing and deleting products as well.

Low-level Cache API Methods

Thus far, we've used the cache.get, cache.set, and cache.delete methods to get, set, and delete (for invalidation) objects in the cache. Let's take a look at some more methods from django.core.cache.cache.

cache.get_or_set

Gets the specified key if present. If it's not present, it sets the key.

Syntax

cache.get_or_set(key, default, timeout=DEFAULT_TIMEOUT, version=None)

The timeout parameter is used to set for how long (in seconds) the cache will be valid. Setting it to None will cache the value forever. Omitting it will use the timeout, if any, that is set in setting.py in the CACHES setting

Many of the cache methods also include a version parameter. With this parameter you can set or access different versions of the same cache key.

Example

>>> from django.core.cache import cache

>>> cache.get_or_set('my_key', 'my new value')

'my new value'

We could have used this in our view instead of using the if statements:

# current implementation

product_objects = cache.get('product_objects')

if product_objects is None:

product_objects = Product.objects.all()

cache.set('product_objects', product_objects)

# with get_or_set

product_objects = cache.get_or_set('product_objects', product_objects)

cache.set_many

Used to set multiple keys at once by passing a dictionary of key-value pairs.

Syntax

cache.set_many(dict, timeout)

Example

>>> cache.set_many({'my_first_key': 1, 'my_second_key': 2, 'my_third_key': 3})

cache.get_many

Used to get multiple cache objects at once. It returns a dictionary with the keys specified as parameters to the method, as long as they exist and haven't expired.

Syntax

cache.get_many(keys, version=None)

Example

>>> cache.get_many(['my_key', 'my_first_key', 'my_second_key', 'my_third_key'])

OrderedDict([('my_key', 'my new value'), ('my_first_key', 1), ('my_second_key', 2), ('my_third_key', 3)])

cache.touch

If you want to update the expiration for a certain key, you can use this method. The timeout value is set in the timeout parameter in seconds.

Syntax

cache.touch(key, timeout=DEFAULT_TIMEOUT, version=None)

Example

>>> cache.set('sample', 'just a sample', timeout=120)

>>> cache.touch('sample', timeout=180)

cache.incr and cache.decr

These two methods can be used to increment or decrement a value of a key that already exists. If the methods are used on a nonexistent cache key it will return a ValueError.

In the case of not specifying the delta parameter the value will be increased/decreased by 1.

Syntax

cache.incr(key, delta=1, version=None)

cache.decr(key, delta=1, version=None)

Example

>>> cache.set('my_first_key', 1)

>>> cache.incr('my_first_key')

2

>>>

>>> cache.incr('my_first_key', 10)

12

cache.close()

To close the connection to your cache you use the close() method.

Syntax

cache.close()

Example

cache.close()

cache.clear

To delete all the keys in the cache at once you can use this method. Just keep in mind that it will remove everything from the cache, not just the keys your application has set.

Syntax

cache.clear()

Example

cache.clear()

Conclusion

In this article, we looked at the low-level cache API in Django. We extended a demo project to use low-level caching and also invalidated the cache using Django's database signals and the Django Lifecycle hooks third-party package.

We also provided an overview of all the available methods in the Django low-level cache API together with examples of how to use them.

You can find the final code in the django-low-level-cache repo.

--

Django Caching Articles:

- Caching in Django

- Low-Level Cache API in Django (this article!)

J-O Eriksson

J-O Eriksson