This article serves as a guide to testing Flask applications with pytest.

We'll first look at why testing is important for creating maintainable software and what you should focus on when testing. Then, we'll detail how to:

- Create and run Flask-specific unit and functional tests with pytest

- Utilize fixtures to initialize the state for test functions

- Check the coverage of the tests using coverage.py

The source code (along with detailed installation instructions) for the Flask app being tested in this article can be found on GitLab at https://gitlab.com/patkennedy79/flask_user_management_example.

Contents

Objectives

By the end of this article, you will be able to:

- Explain what to test in a Flask app

- Describe the differences between pytest and unittest

- Write Flask-specific unit and functional test functions with pytest

- Run tests with pytest

- Create fixtures for initializing the state for test functions

- Determine code coverage of your tests with coverage.py

Why Write Tests?

In general, testing helps ensure that your app will work as expected for your end users.

Software projects with high test coverage are never perfect, but it's a good initial indicator of the quality of the software. Additionally, testable code is generally a sign of a good software architecture, which is why advanced developers take testing into account throughout the entire development lifecycle.

Tests can be considered at three levels:

- Unit

- Functional (or integration)

- End-to-end

Unit tests test the functionality of an individual unit of code isolated from its dependencies. They are the first line of defense against errors and inconsistencies in your codebase. They test from the inside out, from the programmer's point of view.

Functional tests test multiple components of a software product to make sure the components are working together properly. Typically, these tests focus on functionality that the user will be utilizing. They test from the outside in, from the end user's point of view.

Both unit and functional testing are fundamental parts of the Test-Driven Development (TDD) process.

Testing improves the maintainability of your code.

Maintainability refers to making bug fixes or enhancements to your code or to another developer needing to update your code at some point in the future.

Testing should be combined with a Continuous Integration (CI) process to ensure that your tests are constantly being executed, ideally on each commit to your repository. A solid suite of tests can be critical to catching defects quickly and early in the development process before your end users come across them in production.

What to Test?

What should you test?

Again, unit tests should focus on testing small units of code in isolation.

For example, in a Flask app, you may use unit tests to test:

- Database models (often defined in models.py)

- Utility functions (for example, server-side validation checks) that your view functions call

Functional tests, meanwhile, should focus on how the view functions operate.

For example:

- Nominal conditions (GET, POST, etc.) for a view function

- Invalid HTTP methods are handled properly for a view function

- Invalid data is passed to a view function

Focus on testing scenarios that the end user will interact with. The experience that the users of your product have is paramount!

pytest vs. unittest

pytest is a test framework for Python used to write, organize, and run test cases. After setting up your basic test structure, pytest makes it easy to write tests and provides a lot of flexibility for running the tests. pytest satisfies the key aspects of a good test environment:

- tests are fun to write

- tests can be written quickly by using helper functions (fixtures)

- tests can be executed with a single command

- tests run quickly

pytest is incredible! I highly recommend using it for testing any application or script written in Python.

If you're interested in really learning all the different aspects of pytest, I highly recommend the Python Testing with pytest book by Brian Okken.

Python has a built-in test framework called unittest, which is a great choice for testing as well. The unittest module is inspired by the xUnit test framework.

It provides the following:

- tools for building unit tests, including a full suite of

assertstatements for performing checks - structure for developing unit tests and unit test suites

- test runner for executing tests

The main differences between pytest and unittest:

| Feature | pytest | unittest |

|---|---|---|

| Installation | Third-party library | Part of the core standard library |

| Test setup and teardown | fixtures | setUp() and tearDown() methods |

| Assertion Format | Built-in assert | assert* style methods |

| Structure | Functional | Object-oriented |

Either framework is good for testing a Flask project. However, I prefer pytest since it:

- Requires less boilerplate code so your test suites will be more readable.

- Supports the plain

assertstatement, which is far more readable and easier to remember compared to theassertSomethingmethods -- likeassertEquals,assertTrue, andassertContains-- in unittest. - Is updated more frequently since it's not part of the Python standard library.

- Simplifies setting up and tearing down test state.

- Uses a functional approach.

- Supports fixtures.

Testing

Project Structure

I like to organize all the test cases in a separate "tests" folder at the same level as the application files.

Additionally, I really like differentiating between unit and functional tests by splitting them out as separate sub-folders. This structure gives you the flexibility to easily run just the unit tests (or just the functional tests, for that matter).

Here's an example of the structure of the "tests" directory:

└── tests

├── conftest.py

├── functional

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── test_books.py

│ └── test_users.py

└── unit

├── __init__.py

└── test_models.py

And, here's how the "tests" folder fits into a typical Flask project with blueprints:

├── app.py

├── project

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── models.py

│ └── ...blueprint folders...

├── requirements.txt

├── tests

│ ├── conftest.py

│ ├── functional

│ │ ├── __init__.py

│ │ ├── test_books.py

│ │ └── test_users.py

│ └── unit

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── test_models.py

└── venv

Unit Test Example

The first test that we're going to write is a unit test for project/models.py, which contains the SQLAlchemy interface to the database.

This test doesn't access the underlying database; it only checks the interface class used by SQLAlchemy.

Since this test is a unit test, it should be implemented in tests/unit/test_models.py:

from project.models import User

def test_new_user():

"""

GIVEN a User model

WHEN a new User is created

THEN check the email, hashed_password, and role fields are defined correctly

"""

user = User('[email protected]', 'FlaskIsAwesome')

assert user.email == '[email protected]'

assert user.hashed_password != 'FlaskIsAwesome'

assert user.role == 'user'

Let's take a closer look at this test.

After the import, we start with a description of what the test does:

"""

GIVEN a User model

WHEN a new User is created

THEN check the email, hashed_password, and role fields are defined correctly

"""

Why include so many comments for a test function?

I've found that tests are one of the most difficult aspects of a project to maintain. Often, the code (including the level of comments) for test suites is nowhere near the level of quality as the code being tested.

A common structure used to describe what each test function does helps with maintainability by making it easier for someone (another developer, your future self) to quickly understand the purpose of each test.

A common practice is to use the GIVEN-WHEN-THEN structure:

- GIVEN - what are the initial conditions for the test?

- WHEN - what is occurring that needs to be tested?

- THEN - what is the expected response?

For more, review the GivenWhenThen article by Martin Fowler and the Python Testing with pytest book by Brian Okken.

Next, we have the actual test:

user = User('[email protected]', 'FlaskIsAwesome')

assert user.email == '[email protected]'

assert user.hashed_password != 'FlaskIsAwesome'

assert user.role == 'user'

After creating a new user with valid arguments to the constructor, the properties of the user are checked to make sure it was created properly.

Functional Test Examples

The second test that we're going to write is a functional test for project/books/routes.py, which contains the view functions for the books blueprint.

Since this test is a functional test, it should be implemented in tests/functional/test_books.py:

from project import create_app

def test_home_page():

"""

GIVEN a Flask application configured for testing

WHEN the '/' page is requested (GET)

THEN check that the response is valid

"""

# Set the Testing configuration prior to creating the Flask application

os.environ['CONFIG_TYPE'] = 'config.TestingConfig'

flask_app = create_app()

# Create a test client using the Flask application configured for testing

with flask_app.test_client() as test_client:

response = test_client.get('/')

assert response.status_code == 200

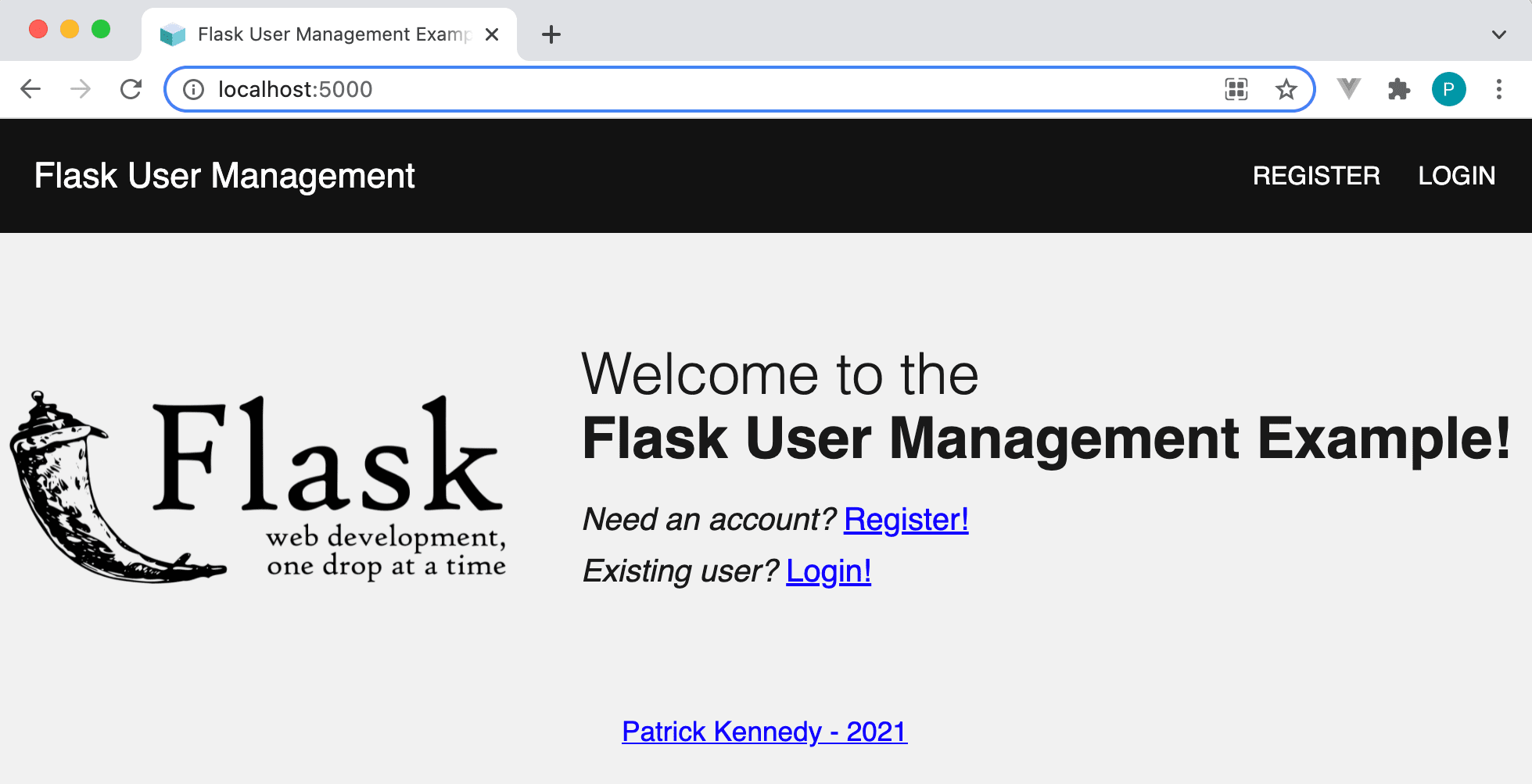

assert b"Welcome to the" in response.data

assert b"Flask User Management Example!" in response.data

assert b"Need an account?" in response.data

assert b"Existing user?" in response.data

This project uses the Application Factory Pattern to create the Flask application. Therefore, the create_app() function needs to first be imported:

from project import create_app

The test function, test_home_page(), starts with the GIVEN-WHEN-THEN description of what the test does. Next, a Flask application (flask_app) is created:

# Set the Testing configuration prior to creating the Flask application

os.environ['CONFIG_TYPE'] = 'config.TestingConfig'

flask_app = create_app()

The test function sets the CONFIG_TYPE environment variable to specify the testing configuration (based on the TestingConfig class specified in config.py. This step is critical, as many Flask extensions (in particular, Flask-SQLAlchemy) will only read the configuration variables during initialization (i.e., init_app(app)).

NOTE: Setting the

CONFIG_TYPEenvironment variable usingos.environ[]will only set the environment variable while the current process (i.e., the Python interpreter) is running.

To create the proper environment for testing, Flask provides a test_client helper:

# Create a test client using the Flask application configured for testing

with flask_app.test_client() as test_client:

....

This creates a test version of our Flask application, which we used to make a GET call to the '/' URL. We then check that the status code returned is OK (200) and that the response contained the following strings:

- Welcome to the Flask User Management Example!

- Need an account?

- Existing user?

These checks match with what we expect the user to see when we navigate to the '/' URL:

An example of an off-nominal functional test would be to utilize an invalid HTTP method (POST) when accessing the '/' URL:

def test_home_page_post():

"""

GIVEN a Flask application configured for testing

WHEN the '/' page is posted to (POST)

THEN check that a '405' (Method Not Allowed) status code is returned

"""

# Set the Testing configuration prior to creating the Flask application

os.environ['CONFIG_TYPE'] = 'config.TestingConfig'

flask_app = create_app()

# Create a test client using the Flask application configured for testing

with flask_app.test_client() as test_client:

response = test_client.post('/')

assert response.status_code == 405

assert b"Flask User Management Example!" not in response.data

This test checks that a POST request to the '/' URL results in an error code of 405 (Method Not Allowed) being returned.

Take a second to review the two functional tests... do you see some duplicate code between these two test functions? Do you see a lot of code for initializing the state needed by the test functions? We can use fixtures to address these issues.

Fixtures

Fixtures initialize tests to a known state to run tests in a predictable and repeatable manner.

xUnit

The classic approach to writing and executing tests follows the xUnit type of test framework, where each test runs as follows:

SetUp()- ...run the test case...

TearDown()

The SetUp() and TearDown() methods always run for each unit test within a test suite. This approach results in the same initial state for each test within a test suite, which doesn't provide much flexibility.

Advantages of Fixtures

The test fixture approach provides much greater flexibility than the classic Setup/Teardown approach.

pytest-flask facilitates testing Flask apps by providing a set of common fixtures used for testing Flask apps. This library is not used in this tutorial, as I want to show how to create the fixtures that help support testing Flask apps.

First, fixtures are defined as functions (that should have a descriptive name for their purpose).

Second, multiple fixtures can be run to set the initial state for a test function. In fact, fixtures can even call other fixtures! So, you can compose them together to create the required state.

Finally, fixtures can be run with different scopes:

function- run once per test function (default scope)class- run once per test classmodule- run once per module (e.g., a test file)session- run once per session

For example, if you have a fixture with module scope, that fixture will run once (and only once) before the test functions in the module run.

Fixtures should be created in tests/conftest.py.

Unit Test Example

To help facilitate testing the User class in project/models.py, we can add a fixture to tests/conftest.py that is used to create a User object to test:

from project.models import User

@pytest.fixture(scope='module')

def new_user():

user = User('[email protected]', 'FlaskIsAwesome')

return user

The @pytest.fixture decorator specifies that this function is a fixture with module-level scope. In other words, this fixture will be called one per test module.

This fixture, new_user, creates an instance of User using valid arguments to the constructor. user is then passed to the test function (return user).

We can simplify the test_new_user() test function from earlier by using the new_user fixture in tests/unit/test_models.py:

def test_new_user_with_fixture(new_user):

"""

GIVEN a User model

WHEN a new User is created

THEN check the email, hashed_password, and role fields are defined correctly

"""

assert new_user.email == '[email protected]'

assert new_user.hashed_password != 'FlaskIsAwesome'

assert new_user.role == 'user'

By using a fixture, the test function is reduced to the assert statements that perform the checks against the User object.

Functional Test Examples

Fixture

To help facilitate testing all the view functions in the Flask project, a fixture can be created in tests/conftest.py:

import os

from project import create_app

@pytest.fixture(scope='module')

def test_client():

# Set the Testing configuration prior to creating the Flask application

os.environ['CONFIG_TYPE'] = 'config.TestingConfig'

flask_app = create_app()

# Create a test client using the Flask application configured for testing

with flask_app.test_client() as testing_client:

# Establish an application context

with flask_app.app_context():

yield testing_client # this is where the testing happens!

This fixture creates the test client using a context manager:

with flask_app.test_client() as testing_client:

Next, the Application context is pushed onto the stack for use by the test functions:

with flask_app.app_context():

yield testing_client # this is where the testing happens!

To learn more about the Application context in Flask, refer to the following blog posts:

The yield testing_client statement means that execution is being passed to the test functions.

Using the Fixture

We can simplify the functional tests from earlier with the test_client fixture in tests/functional/test_books.py:

def test_home_page_with_fixture(test_client):

"""

GIVEN a Flask application configured for testing

WHEN the '/' page is requested (GET)

THEN check that the response is valid

"""

response = test_client.get('/')

assert response.status_code == 200

assert b"Welcome to the" in response.data

assert b"Flask User Management Example!" in response.data

assert b"Need an account?" in response.data

assert b"Existing user?" in response.data

def test_home_page_post_with_fixture(test_client):

"""

GIVEN a Flask application configured for testing

WHEN the '/' page is posted to (POST)

THEN check that a '405' (Method Not Allowed) status code is returned

"""

response = test_client.post('/')

assert response.status_code == 405

assert b"Flask User Management Example!" not in response.data

Did you notice that much of the duplicate code is gone? By utilizing the test_client fixture, each test function is simplified down to the HTTP call (GET or POST) and the assert that checks the response.

I find that using fixtures helps to focus the test function on actually doing the testing, as the test initialization is handled in the fixture.

Running the Tests

To run the tests, navigate to the top-level folder of the Flask project and run pytest through the Python interpreter:

(venv)$ python -m pytest

============================= test session starts ==============================

tests/functional/test_books.py .... [ 30%]

tests/functional/test_users.py ..... [ 69%]

tests/unit/test_models.py .... [100%]

============================== 13 passed in 0.46s ==============================

Why run pytest through the Python interpreter?

The main advantage is that the current directory (e.g., the top-level folder of the Flask project) is added to the system path. This avoids any problems with pytest not being able to find the source code.

pytest will recursively search through your project structure to find the Python files that start with test_*.py and then run the functions that start with test_ in those files. There is no configuration needed to identify where the test files are located!

To see more details on the tests that were run:

(venv)$ python -m pytest -v

============================= test session starts ==============================

tests/functional/test_books.py::test_home_page PASSED [ 7%]

tests/functional/test_books.py::test_home_page_post PASSED [ 15%]

tests/functional/test_books.py::test_home_page_with_fixture PASSED [ 23%]

tests/functional/test_books.py::test_home_page_post_with_fixture PASSED [ 30%]

tests/functional/test_users.py::test_login_page PASSED [ 38%]

tests/functional/test_users.py::test_valid_login_logout PASSED [ 46%]

tests/functional/test_users.py::test_invalid_login PASSED [ 53%]

tests/functional/test_users.py::test_valid_registration PASSED [ 61%]

tests/functional/test_users.py::test_invalid_registration PASSED [ 69%]

tests/unit/test_models.py::test_new_user PASSED [ 76%]

tests/unit/test_models.py::test_new_user_with_fixture PASSED [ 84%]

tests/unit/test_models.py::test_setting_password PASSED [ 92%]

tests/unit/test_models.py::test_user_id PASSED [100%]

============================== 13 passed in 0.62s ==============================

If you only want to run a specific type of test:

python -m pytest tests/unit/python -m pytest tests/functional/

If you are seeing a lot of warnings about deprecated features in Python packages that you're utilizing, you can hide all the warning printouts using:

python -m pytest --disable-warnings

Fixtures in Action

To really get a sense of when the test_client() fixture is run, pytest can provide a call structure of the fixtures and tests with the --setup-show argument:

(venv)$ python -m pytest --setup-show tests/functional/test_books.py

====================================== test session starts =====================================

tests/functional/test_books.py

...

SETUP M test_client

functional/test_books.py::test_home_page_with_fixture (fixtures used: test_client).

functional/test_books.py::test_home_page_post_with_fixture (fixtures used: test_client).

TEARDOWN M test_client

======================================= 4 passed in 0.18s ======================================

The test_client fixture has a 'module' scope, so it's executed prior to the two _with_fixture tests in tests/functional/test_books.py.

If you change the scope of the test_client fixture to a 'function' scope:

@pytest.fixture(scope='function')

Then the test_client fixture will run prior to each of the two _with_fixture tests:

(venv)$ python -m pytest --setup-show tests/functional/test_books.py

======================================= test session starts ======================================

tests/functional/test_books.py

...

SETUP F test_client

functional/test_books.py::test_home_page_with_fixture (fixtures used: test_client).

TEARDOWN F test_client

SETUP F test_client

functional/test_books.py::test_home_page_post_with_fixture (fixtures used: test_client).

TEARDOWN F test_client

======================================== 4 passed in 0.21s =======================================

Since we want the test_client fixture to only be run once in this module, revert the scope back to 'module'.

Code Coverage

When developing tests, it's nice to get an understanding of how much of the source code is actually tested. This concept is known as code coverage.

I need to be very clear that having a set of tests that covers 100% of the source code is by no means an indicator that the code is properly tested.

This metric means that there are a lot of tests and a lot of effort has been put into developing the tests. The quality of the tests still needs to be checked by code inspection.

That said, the other extreme, where this is a minimal set (or none!) of tests, is much worse!

There are two excellent packages available for determining code coverage: coverage.py and pytest-cov.

I recommend using pytest-cov based on its seamless integration with pytest. It's built on top of coverage.py, from Ned Batchelder, which is the standard in code coverage for Python.

Running pytest when checking for code coverage requires the --cov argument to indicate which Python package (project in the Flask project structure) to check the coverage of:

(venv)$ python -m pytest --cov=project

============================= test session starts ==============================

tests/functional/test_books.py .... [ 30%]

tests/functional/test_users.py ..... [ 69%]

tests/unit/test_models.py .... [100%]

---------- coverage: platform darwin, python 3.8.5-final-0 -----------

Name Stmts Miss Cover

-------------------------------------------------

project/__init__.py 27 0 100%

project/models.py 32 2 94%

project/books/__init__.py 3 0 100%

project/books/routes.py 5 0 100%

project/users/__init__.py 3 0 100%

project/users/forms.py 18 1 94%

project/users/routes.py 50 4 92%

-------------------------------------------------

TOTAL 138 7 95%

============================== 13 passed in 0.86s ==============================

Even when checking code coverage, arguments can still be passed to pytest:

(venv)$ python -m pytest --setup-show --cov=project

Conclusion

This article served as a guide for testing Flask applications, focusing on:

- Why you should write tests

- What you should test

- How to write unit and functional tests

- How to run tests using pytest

- How to create fixtures to initialize the state for test functions

If you're interested in learning more about Flask, check out my course on how to build, test, and deploy Flask applications:

Patrick Kennedy

Patrick Kennedy